An essay by Michelle J. Smith, Monash University, School of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics, Faculty Member Deakin University, School of Communication and Creative Arts, Post-Doc

Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is one of the most popular children’s books in history – it has inspired a curious visual dreamscape that has expanded far beyond the words found in its pages; a blank surface onto which we can project and explore any dream, vision, or anxiety, with the simple sight of a playing card, pocket watch, or tea party. Alice is a key to the cultural imagination of the strangest and most beautiful visual worlds, however fantastic.

Alice’s curiosity came to symbolise the widest reaches of psychological possibility and imagination in the 1960s. Jefferson Airplane made metaphorical use of the story in their psychedelic paean to drug use. In response, the National Institute of Mental Health in the USA figured that Alice’s adventures in a trippy realm of heroin, speed, and a weed-smoking caterpillar could also deter children from experimenting with mind-altering substances.

Alice Au Pays des Merveilles (1949), courtesy of Lou Bunin Productions.

Alice Au Pays des Merveilles (1949), courtesy of Lou Bunin Productions.

Wonderland collapses the division between the waking world and the realm of dreams. It dissolves the borders between the real and the unreal. On film Alice can manifest as a cryptic clue in science-fiction, with the white rabbit leading The Matrix’s Neo out of a dream world and into reality. She can transform from a doll into a human in a dark surrealist imagining, or sing and dance her way through a musical. With the constant confusion of her dramatic transformations in size, Alice also embodies the difficulties of growing older and the awkwardness of adolescence. In fantasy stories about boys, usually they grow up—their journey leading them to maturity.

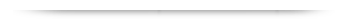

Alice in Wonderland magic lantern slides (1905-1908), W. Butcher & Sons, courtesy Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

Alice in Wonderland magic lantern slides (1905-1908), W. Butcher & Sons, courtesy Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

Fantastic girls like Alice, however, tend not to develop as a result of their experiences. Instead, she is highly symbolic. Alice’s ambiguous nature means we have put her to use to express innumerable hopes and fears. In popular music, she has been used to celebrate individuality, embody female sexuality, and, as a metaphor for the search for creative inspiration. In Japan, Alice maps perfectly onto the idealised figure of the ‘shojo’, or girl, who occupies the space between child and adult. Her cuteness and innocence often serve as a foil for K-pop and J-pop boy bands.

Japan’s embrace of Alice has enabled the merger of a fascination with Victorian England with the modern genre of anime. Just like Betty Boop, kawaii cartoon figure Hello Kitty has also been transported to Wonderland. But she is most definitely not cut out for the illogical adults who reside there. Although she is often depicted as a woman on screen, Carroll’s Alice was only seven years old. While her blue or yellow dress and pinafore are relatively unchanging, the wild possibilities of Wonderland are a fertile ground for high fashion and beauty brands who wish to convey innovation and their embrace of the strange and unusual.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, (1910).

Alice can be mobilised as a prim and polite figure to advocate for the merits of Dr Pepper or be called on as a key to gain entry to a magical world of glamorous products and sophisticated people. The world inside the book or through the looking glass can contain anything that we desire, including an ideal version of ourselves.

While early games recreated the tone of the novel, Alice has since come to embody some of our darker fantasies. Alice is now commonly reoriented within stories for adults. She can embody innocent discovery of the enchanting and unfamiliar. Yet in a time of cultural upheaval Alice can now be represented as mentally disturbed or murderous. This contrasts with her traditional role as a bastion of sanity among “all mad” characters. These dark visual manifestations reconfigure Alice in ways that Carroll never imagined.

Alice (1988), courtesy Athanor Film Production Company Ltd.

Whatever kind of Alice we need in any time, place, or culture, for audiences young or old, we can create by using the template of one girl’s encounters within a dreamscape. The curious world of Wonderland is a cultural silver screen onto which we can project images of anything we desire, however fantastic.